What price would you pay to fight tyranny?

“… every deed that does good must do harm somewhere else. This recognition of the ‘double-edge of the deed’, leads many people… to swear off acting at all… but man cannot live without guilt… therefore we must have the courage to accept guilt and responsibility” Hans Litten, 1925.

We have again secured another amateur premiere of a brand new play which only completed its West End run in March 2015 to rave reviews.

It is based on the true story of a brilliant lawyer, Hans Litten, who in 1931 called Adolf Hitler to act as star witness in the trial of a band of murderous SA men. Two years later, Litten is arrested. He is held without trial, beaten, tortured, and threatened as 'an enemy of human society'.

His story is told by his mother Irmgard who confronts his captors and fights to try and achieve his release (played in the West End production by Penelope Wilton). Ultimately inspirational, the play reminds us of the importance of protecting human rights and freedom of expression, and the high price of resisting tyranny.

Anne-marie Greene (Mindgame, Proof, Let the Right One In) directs this compelling drama.

There seems to be a renewed interest in Nazi Germany at the moment, particularly on TV, no doubt linked to the rise of right-wing populism in Europe and America. But Mark Hayhurst’s play set in 1930s Germany is less about tyranny than the cost of resistance.

Two true stories play out side by side in this harrowing production. One is the story of Hans Litten (Gareth Withers), a Jewish lawyer who had the audacity to subpoena Adolf Hitler in a trial of four of his foot soldiers accused of murder in 1931. Litten was a clever, slightly vain lawyer, who enjoyed the spectacle of the courtroom and made a fool of Hitler in the witness box. Hitler never forgot the insult, and in 1933 Litten was arrested and incarcerated in a series of concentration camps “for his own protection”. There he suffered the fate of many, many more that were worked to death or simply annihilated, out of sight and out of mind.

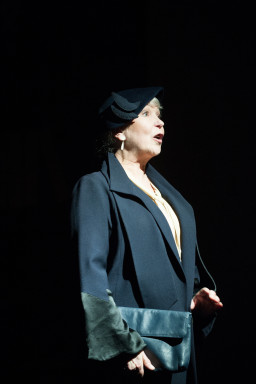

The other story is that of his mother, Irmgard Litten (Deb Relton-Elves), a wealthy aristocratic woman who never gave up in the fight for his release, often without the support of her own family. Hers is a story of a mother’s love that knows no bounds, desperately seeking for a way around the Party’s obstinacy. Her resistance is expressed through her relationship with Dr Conrad (Jon Elves), a senior Gestapo officer who holds the keys to her son’s release and with whom over time she forms an almost intimate relationship as they play cat and mouse in his office. But he is forever the cat: beneath their civilised discourse there is more than a touch of sadism in the way he plays her for the Party’s good.

Irmgard is really the centre of this play, and her lonely fight is deeply moving to behold. Deb Relton-Elves delivers a fine performance, passionate, upright and intelligent. She is ably supported by Gareth Withers as Hans, who reminded me not a little of Kenneth Branagh in his delivery. Two other opponents of tyranny share Hans’ cell and his punishments: the anarchist Erich Muhsam (Dave Crossfield) who bitingly mocks the absurdity of the Nazi ego, and Carl von Ossietzky (George Rippon), who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1935 for his exposure of the secret German rearmaments programme. On stage they form a tragic, heroic triumvirate. Matt Sweatman is marvellously pompous as Hans’ father Fritz, a former university chancellor who is sacked for his Jewish background and who yet continues to urge compromise. Perhaps most disturbing is Steve Brown as Lord Clifford Allen, the tall angular British diplomat and former pacifist who, in those years of appeasement, tries not to rock the Nazi boat too hard and thus conspires in Hans’ death.

Mark Hayhurst has made a career out of writing about Hans Litton. This is a deeply disturbing play that raises difficult questions and touches many nerve endings today.

Just when you thought that everything that could have been said had been said about Germany in the 1930s, along comes a play that gets to the heart of what it took for individual Germans to question and resist the rise of Nazi power. And that immediately raises another question for members of the audience: how far would I have gone in the circumstances?

At the heart of Taken at Midnight is the relationship between Irmgard Litten and her son, Hans, a brilliant young lawyer who had made the mistake of humiliating one Adolf Hitler during a court case in 1931. Two years later, Hans has been moved from courtroom to courtyard – a prison courtyard where he is beaten and tortured. He is not alone.

Anne-marie Greene’s direction makes the most of a cleverly adaptive set that switches swiftly between the domestic, the official and the brutally judicial.

Chris Arnot

Another tour de force from actors at the the Criterion led by

Director Anne-marie Greene is right when she says not many of us know about the true story of Hans Litten, the German lawyer who had the audacity to summon

This dramatisation of

The Criterion is the first non-professional company to stage this powerful play which follows the fate of Litten despite the unflagging efforts of his well-connected mother who won support from senor German officials, British diplomats and even Prince Wilhelm of Prussia.

Really it's her story, told with elegance and

There was some loss of dramatic edge during Act Two with a couple of overlong scenes - but none involving Gareth Withers, who commands even the smallest stage space he's forced to occupy.

As Litten rots in "protective custody"

Barbara Goulden

https://www.elementarywhatson.com