WOULD YOU RECOGNISE A MIRACLE IF YOU SAW ONE?

EDI Assessment

In line with our new EDI policy, we undertake an EDI impact assessment of all our artistic programming. 'Underneath the Lintel' -The character of the librarian is Jewish and elderly and there could be flexibility around race/ethnicity. Has to be played as a male character. The story includes a theme of the consequences of anti-Semitic discrimination.

Review by Nick Le Mesurier

Glen Berger’s one-man play, Underneath The Lintel, made a surprise hit in 2007 when it was played in the West End by Richard Schiff, who played Toby Zeigler in the long running series The West Wing. Previously it had enjoyed a successful run off-Broadway, drawing praises from all quarters. The UK press was more divided, some claiming it to be one of the best plays of the year, others with more contrary views.

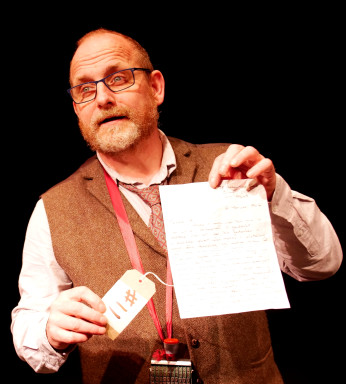

For sure, the premise does not seem to grab the attention. A lonely old man, a former librarian in Holland, has come to give a one-off lecture on a series of extraordinary events in his life. They tell of a quest to find the identity of someone who returned a book 113 years after it was due. What transpires turns out to be a revelatory experience.

I won’t say more about the plot, which is intriguing in its labyrinthine intricacies and bizarre coincidences. Suffice it to say that as he picks up little clue after little clue, he comes to realise an age-old secret, in part about a mysterious figure who haunts the story, but more significantly about life’s essential connectivity. Slowly, layer by layer, he builds a picture that takes him all over the world, in what amounts to a marvellous shaggy dog story. From little details, one might say, mighty themes do grow.

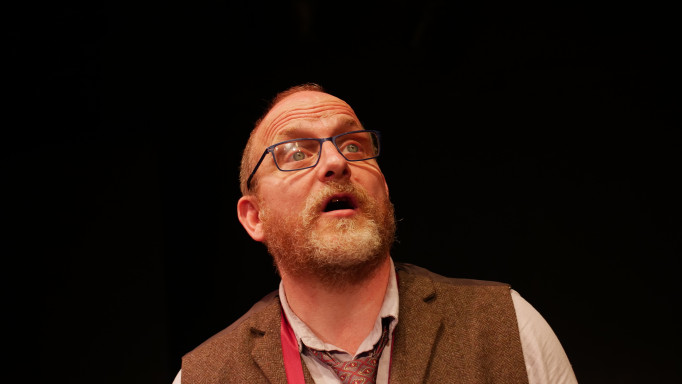

The glory of this production is undoubtedly in Jon Elves’s magnificent portrayal of the little Dutchman. For ninety minutes he held us spellbound, aided only by a blackboard and a suitcase full of items, evidence as he calls them, of the truth of his story. He plays the part with all the enthusiasm of a man who has experienced a revelation, an insight into life’s essential mystery. But he is no preacher; his character’s modesty is part of the charm.

If I have a few qualms, it is mainly with the use of slide projections and music to indicate a change of scene. So strong is the narrative I’m not sure these were necessary. What is beyond doubt is that Jon Elves gives one of the finest, most engaging performances on the local stage I have seen in a long time.

Review by Chris Arnot

Sometime in the mid-1930s a book was borrowed from Earlsdon Library by a pupil from King Henry VIII School. It was finally returned when it was found among his possessions after his death half a century later.

The book was The Senior Commoner by Julian Hall. And the borrower would go on to become the senior librarian at Hull University. Oh yes, and a much-quoted poet. His name was Philip Larkin.

Along the road and round the corner from what is now the Carnegie Community Library, another much-treasured Earlsdon institution is showing a play that evolves from the return of a book 113 years overdue. Yes, more than twice as long as the one “borrowed” by the light-fingered Philip.

In the Criterion’s case, the library is somewhere in provincial Holland and the librarian is one of those frustrated middle-aged men who has done little and travelled nowhere. Until now.

The return of the dusty and somewhat battered Baedeker travel book after a century or so sparks something deep within him. Questions for a start: who returned it and why was it so late?

The only evidence he has to go on is a crumpled bookmark and an unclaimed ticket for a Chinese laundry. What the librarian doesn’t seem short of is money. Then again, he hasn’t had much to spend his wages on.

Having been sacked from the library for taking so much time off, he has hired a theatre to tell the story of his journey into major cities in search of clues and, more importantly, insights into a world beyond bookshelves.

The plot is complex. The setting is sparse. To the right a big screen projects scenes from his visits to New York and Beijing, London and Sydney. To the left an old-fashioned backboard is chalked with dates, including 1986 when the play is set. An equally old-fashioned date-stamper dangles from the librarian’s neck.

Time and space are important in Glen Berger’s play. One of its messages would seem to be the need to make the most of your life when you have the chance. And that seems particularly telling at a time when pandemic restrictions have begun to ease. We need some “expansive moments in restricted lives”, as WH Auden put it in a different context.

One thing’s for certain about the Criterion’s production. Under Richard Warren’s direction, Jon Elves put on an extraordinary one-man show on the opening night. He somehow engaged the audience for an hour and three-quarters – longer than an entire Premier League match, plus injury time with no half-time break.

It was a performance worthy of a theatre 20 miles down the road in the birthplace of a poet and playwright quoted even more often than Auden and Larkin.

Review by Roderic Dunnett (for the full review click here)

The lights have gone up at the Criterion, after far too long off. And this tour-de-force lit up everyone’s evening. How? It was all down to one, or rather two, men, actor and director.

An intriguing, at times puzzling, always involving, and endlessly fascinating, one man show, with a bizarre story, a gradually unfolding mystery, and a great deal of animated activity.

Directed by Criterion regular Richard Warren, and starring – that is certainly the word - Jon Elves... this absorbing stagework dwells on the memories – or perhaps imaginings? – eagerly shared by this one bookish fellow, whose peculiar obsession runs throughout the play, but also provides the takeoff point for much else...

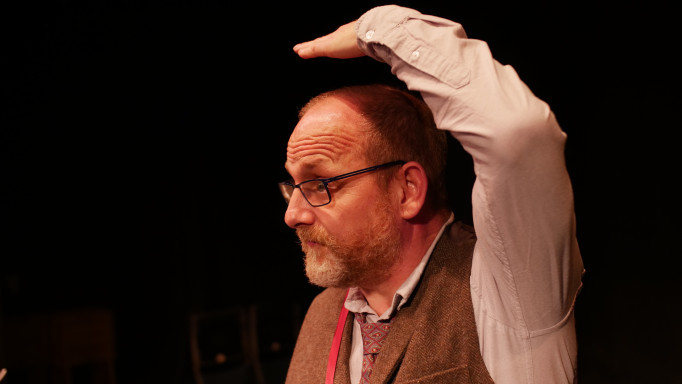

The furnishing is specified as being simple, sparse even, and Props and Set designers Bill Young and Sally Patalong get this somehow perfectly right and apt. We do not need thousands of books to make a rather twee, overloaded set, A lecture room table, of an utterly neutral kind, with a suitcase on it, suffices for this eccentric’s antics – for that is what they are – artfully engineered by Warren and Elves so that somehow the monologue is riddled with action, sometimes mesmerising, always beguiling. We are drawn into this character’s life and preoccupations inexorably. They invite not just our attention, but our active involvement...

That Elves’ character is in reality Jewish seems pretty likely from the start. The way Pam Coleman and Anne-marie (sic) Greene dress the Librarian – essentially browns, with a few additions – somehow suggests it: one half expects him to don scarf and hold out a copy of the Talmud. The fact that he is Dutch might be deemed to make it more likely. Yet despite all, this is not expressly a Jewish figure (though that is the way Berger, one takes it Jewish himself, might initially have conceived, then modified it); but somehow more universal than that. Rather, a Gentile amateur tracker who by coincidence happens to inhabit, or rather light upon, a deepest folk memory (like the Golem, perhaps), of Christian rather than Jewish origin, as is unexpectedly revealed at the close.

The pursuit begins...

What are we to make of all this? Elves’ success in making his character one of us, and of drawing us in, is at the heart of this quite brilliant performance. In its 90 minutes he has as many lines as Prospero or Lear, but he is so abreast of and at ease with them there is not a faltering moment; he lulls us, energises, entertains and amuses us by turns. Above all, we have to take him seriously, as he stresses.

We follow him around as his mood flits and fleets from one emotion to the next. Puzzlement, fascination, determination, disturbedness, insistence, ingenuity; constantly painstaking and methodical. Occasionally (actually quite often) dotty or quirky, which generates the marvellous comedy and bizarreness Elves brings to his frankly fabulous performance. He is a fretful, self-deprecating, usually buoyant if intermittently troubled, yet deeply humane soul, but his affability engenders scarcely any distaste or bitterness or fury (the occasional indignant excitement). And quite free of Jewish or Christian guilt. He is too busy, busy, busy for that...

The Librarian’s always intriguing moves, largely around the desk or table, usually with different speed or gait, or hurtling exuberantly, spasmodically, absentmindedly, often pottily, to front stage, are jerky, here and there frenetic, yet every one somehow underlines the point being made. So carefully plotted are they, it seems clear Warren and Elves have worked endlessly on this script, prising open and peering into every nook and cranny, each nugget of detail, so as to leave no stone unturned, no lintel unaddressed. This is a search without remission, a tenacious, unflagging pursuit from whose very obduracy springs the humour and the infinitely light, rapier-like touch which informs and permeates both this quite breathtaking performance and Berger’s rich, multi-layered text itself...

So, here with Underneath the Lintel was a pairing of truly outstanding talents, both of whom... could easily have made their mark on the professional stage. One was left aghast by this production: the range, the variety, the astonishing deep insights, the perceptiveness of how best to bring it off. At every juncture we were mesmerised, such was the consistent quality of this astounding five-star show. It was an education. I’m so glad I took myself there. I certainly wouldn’t have missed it.